Arthur Szyk’s work resists easy categorization. Few other artists have such a distinctive style, or such a broad range of interests. However, a close examination of his entire body of work reveals that Szyk was particularly focused on four major subject areas: Political Art, Illustrated Tales, Judaica, and National Pride.

About Szyk’s Art

Subject Areas

Political Art

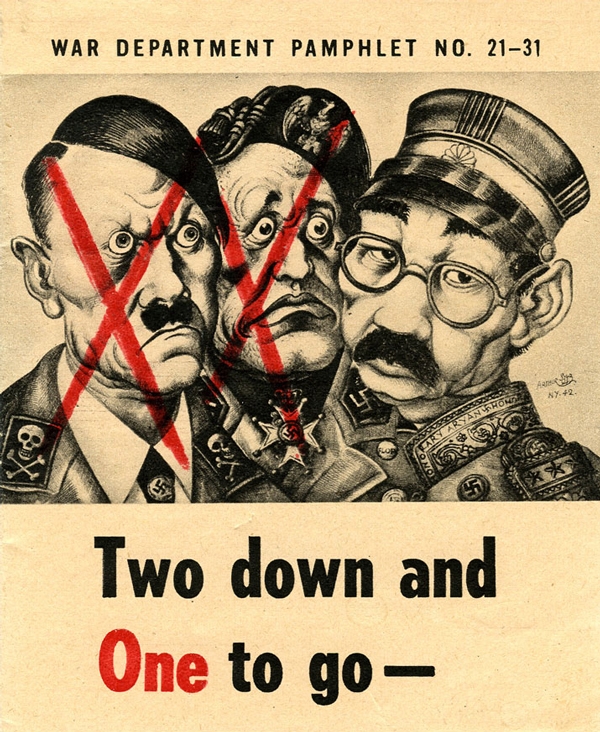

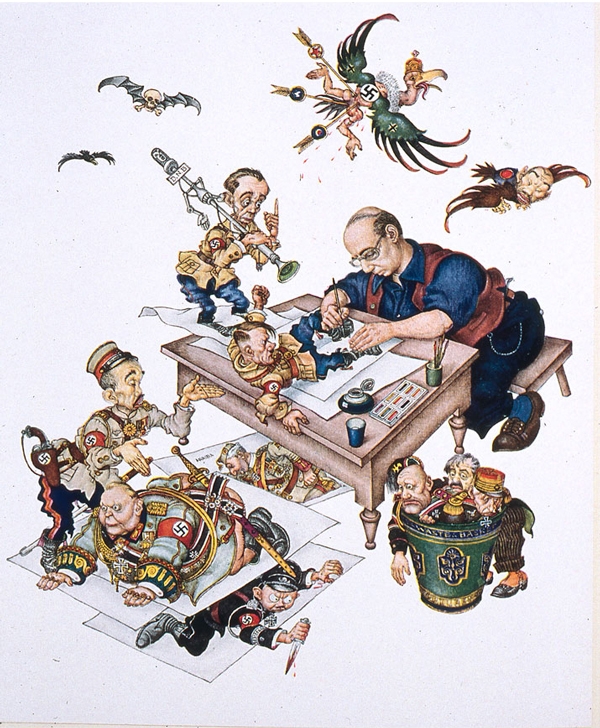

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Szyk focused his energy and talent toward a personal war against Hitler and the Axis. To the surprise of contemporary art critics, his war caricatures—despite the gruesome subject matter—were as beautiful and carefully constructed as his illuminations. From Nazi uniforms to Allied weaponry to military medals, every detail was executed with stunning accuracy.

In keeping with cartooning tradition, Szyk exaggerated faces and postures for effect. He portrayed Goebbels as a shifty rodent, Göring with the proportions of a lumbering gorilla, and Hitler in a number of guises—a barbarian conqueror, a consort of Satan, and a waiter in Valhalla, for example. However, ridicule was not the sole goal of Szyk’s work. He was determined to reveal the brutality and evil of the enemy. For every caricature mocking an incompetent Nazi, another decries the human cost of war, particularly the death of innocent Jewish victims.

Szyk truly was America’s fighting artist, a “one-man army” mobilized to win the war against tyranny and oppression. His political caricatures had an active life in fine art galleries and beyond. Many were published as illustrated books (The New Order and Ink & Blood), magazine covers, newspaper cartoons, and propaganda posters. On the warfront, reproductions of Szyk’s caricatures were distributed among American GIs and proved more popular than pin-up girls.

The vibrancy and power of Szyk’s political art have not faded with time. On the contrary, his work is increasing in significance, for its historical importance as well as its outstanding artistic merits. Many art collectors worldwide count Szyk’s political work among their most prized acquisitions, for no artist then or since has captured the sweep of World War II with more passion and precision.

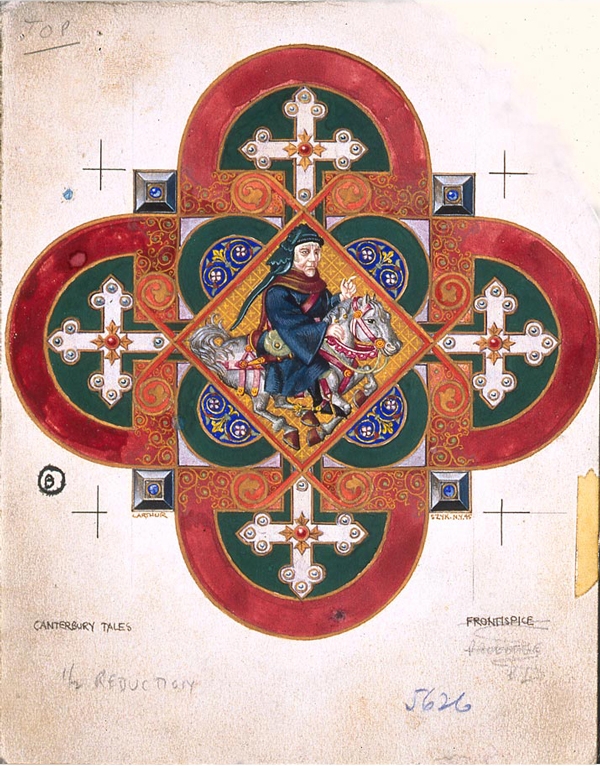

Illustrated Tales

Szyk loved stories, and books of illustrated tales were an ideal way to explore his interest. His illuminated miniatures were perfectly proportioned to the printed page, and, because illustrated books require multiple images, Szyk could create a series for each project—a practice he greatly enjoyed.

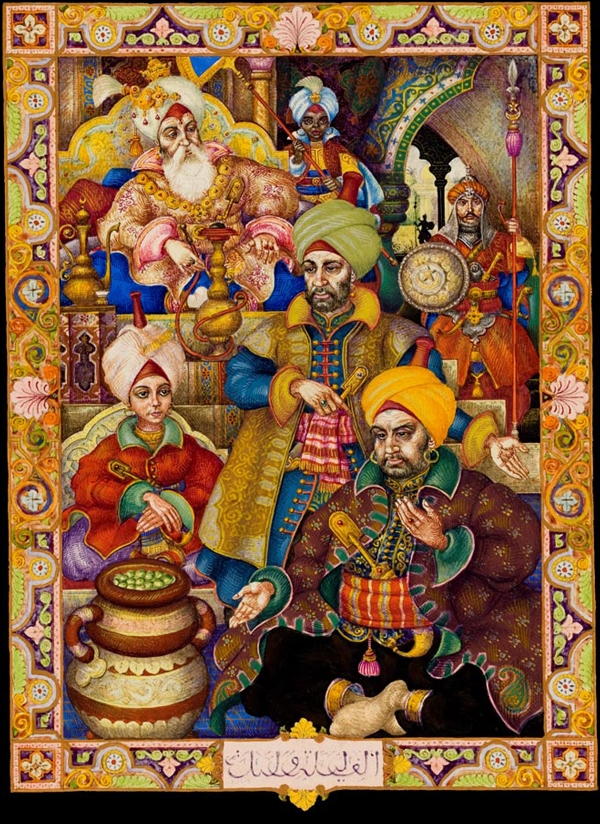

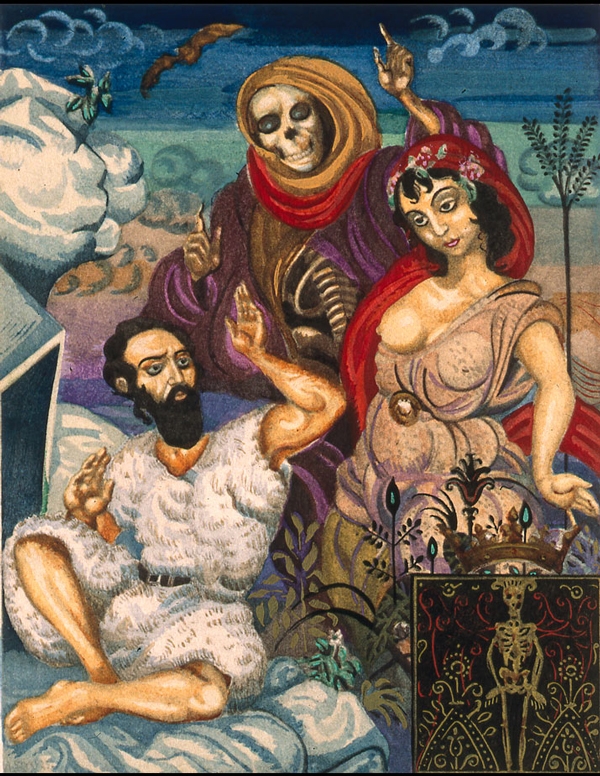

The 30+ books Szyk illustrated in his lifetime are evidence of his versatile style and wide-ranging interests. In a complete reversal from his grim wartime caricatures, the memorable illustrations for Andersen’s Fairy Tales—such as “The Angel”—show Szyk’s childlike imagination at work. He handled contemporary novels like Pierre Benoit’s Le Puits de Jacob as elegantly and respectfully as literary classics like The Canterbury Tales. Szyk mastered styles and visual symbolism of other cultures and faiths to better serve the story at hand. For example, the ornate illuminations of The Arabian Nights Entertainments reveal his mastery of Persian miniature painting, while the fantastical scenes for Gustav Flaubert’s La Tentation de Saint Antoine demonstrate Szyk’s sensitivity to Catholic mysticism.

With the exception of popular mass publications such as Andersen’s Fairy Tales, Szyk’s books were generally published in limited fine art editions. Copies in pristine condition are quite scarce and are desirable additions to any collection. The original works of art for these luxurious volumes are even rarer and are increasingly in demand among collectors.

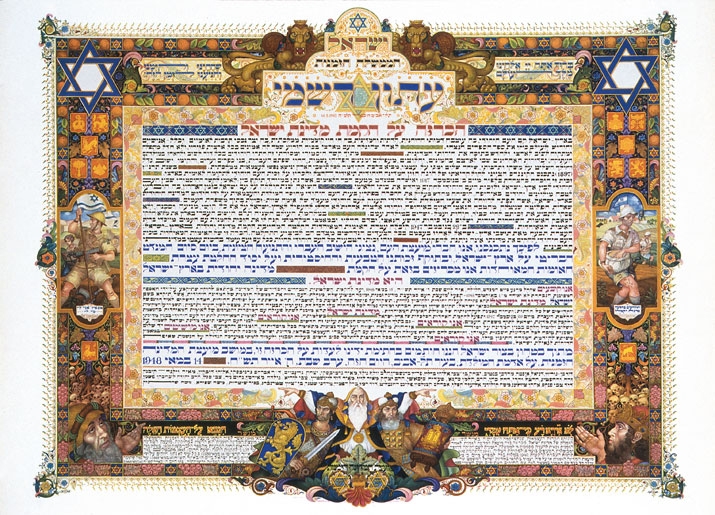

Judaica

Szyk took pride in his Jewish heritage and explored Jewish themes continuously throughout his long career. The literature of The Bible—The Song of Songs, The Book of Ruth, and The Book of Job—provided the perfect complement to his beautiful illuminations. Historical heroes like Moses, Judith, and David, underdogs who defeated tyrants to secure a better life for their people, inspired some of his most memorable work. And his masterful Passover Haggadah is, of course, his greatest work of Judaica.

Yet Szyk’s interest in his heritage was not limited to the triumphs of the past. He was equally moved by the bravery of contemporary Jews, whether they established settlements in Palestine, fought the Nazis in the Warsaw Ghetto, or declared independence for the State of Israel. To emphasize the continuity between the heroes of history and those of the modern world, he fused past and present in the same image. For instance, his masterful Statute of Kalisz places contemporary Polish-Jewish soldiers alongside 13th century kings. In the Szyk Haggadah, the white-bearded, muscular Moses faces down swastika-wearing Egyptians. In Szyk’s tribute to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Jewish fighters are like modern-day Samsons.

Szyk saw his own accomplishments as an outgrowth of his love and devotion to his people. As he once said, “I am but a Jew praying in art, and if I have succeeded to some degree, if I have gain the power of reception among the elite of the world, I owe it all to the teachings, traditions, and eternal virtues of my people.” By extension, the Jewish people owe the most spectacular Judaica of the 20th century to the hand of Arthur Szyk.

National Pride

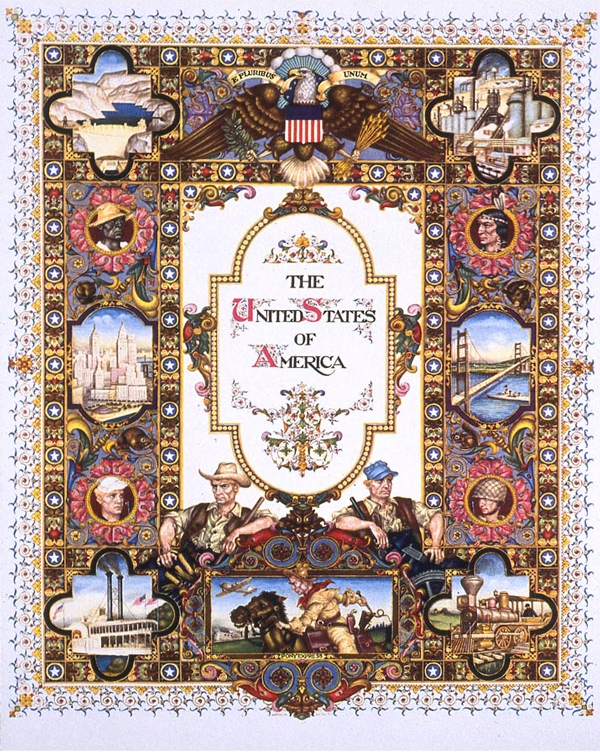

Szyk loved three countries: Poland, the land of his birth; the United States, the land of his ideals; and Israel, the land of his people. These nations and their rich histories—particularly their struggles for democracy and independence—filled him with pride. They also inspired some of his best-known works of art. For instance, it was Szyk’s illumination of the Polish Statute of Kalisz, the 13th century “Jewish Magna Carta,” that first catapulted him to fame in Europe. The series Washington and his Times, which features the heroes of the American War for Independence, earned Szyk his first exhibition in the United States. His beautiful interpretation of Israel’s Proclamation of Independence was widely reproduced and hangs in Jewish homes around the world.

As a “citizen soldier of the free world,” Szyk saw much to celebrate in other countries, too, particularly countries that had won their independence and championed democracy. He created stamps to celebrate the anniversary of the African nation of Liberia. He twice illuminated the history of Canada. Szyk even created a 51-painting series commemorating Simon Bolivar, the “George Washington of South America,” though he himself had never traveled to the continent. Most famously, his Visual History of Nations series pays tribute to many founding members of the United Nations.

It was not enough for Szyk to make his tributes merely beautiful. He aimed for historic accuracy in every project, researching national costumes, regional flags, heraldic symbols, and even wildlife before setting his paintbrush to paper. History and legend were indispensable tools in Szyk’s arsenal. He hunted for the person, event, or document that provided the best parallel to the events of the day. For example, a resurrected Joan of Arc stands at the center of one of his visual tributes to the French. And in illuminations honoring Great Britain, its patron saint St. George—sometimes equipped with modern weaponry—defeats the dragon again and again. By recalling victories of the past, Szyk hoped to inspire national pride and point the way to a victorious future.